The things I should have learned from years of putting together people and technology to get successful product online. We’ll probably talk about strategy, distributed systems, agile development, webscale computing and of course how to manage those most complicated of all machines – the human being – in our quest to expose the most business value in the least expensive way.

Tuesday, 14 July 2015

Career Advice and That Jason Post

Friday, 16 January 2015

The power and the pitfalls of test and learn

Saturday, 17 August 2013

The business value of technology

So what's the justification for good method, design, and computer science? How do you map that academia to real business concerns? A while back I made a handy reference guide for my business buddies:

I don't believe that's comprehensive, but I do believe it's prototypical.

Sunday, 6 January 2013

AI and Travel

- A better user experience; expert guidance through travel planning instead of imposing a significant research burden upon the traveler.

- More intuitive interface which can be entirely cohesive across dissimilar devices.

- Higher conversion rates on sites and apps.

- Faster support for travelers in-trip delivered at a lower cost.

Sunday, 18 September 2011

Nobody cares about your tickets

Tuesday, 7 December 2010

Intellectual Property in 3 posts – episode I

I originally called this ‘Intellectual Property Done Quick’ but, when I was finished and looked at what I had wrought, I realized that ‘done quick’ was likely to be in breach of the trade descriptions act.

So I’ve broken it up into 3 tasty morsels; today I’m doing an introduction to different types of intellectual property and I’ll follow up with applying for a patent and then finally some tips for managing IP in the enterprise.

There are 4 main types of intellectual property defined in UK law and, along with their relatively dry legal descriptions, they are:

Trade marks

Indefinitely protects signs which distinguish the goods or services of one undertaking from those of another.

A trade mark is a distinguishing badge of origin which can be a valuable asset when it imbues a product with the reputation and perception of a certain maker.

It can become a trademark either by initial registration or it can acquire trademark status over time through use.

McDonald’s golden arches, the UPS shield, and Nike’s swoosh are all good examples of a trademark – instantly recognizable and clearly identifying a specific brand.

Registering a trademark gives an organization or an individual the right to prevent others from using the same mark it in relation to similar goods or services (listed in the application). Even if you have no appetite for hunting down and suing IP trespassers, registration is still a good idea because it prevents that happening to you – priority (‘I was already using that before they registered it’) is a tough argument in trade marks. And, in the longer term, if you’re ever likely to want to license the use of your trademark to others then registration establishes an official article against which a license can be granted.

Patents

Protects the technical aspects of products or processes for 20 years.

A patent gives the patent holder exclusive rights to prevent anyone else making, using, or selling their invention for a fixed period of time (usually 20 years) before it becomes part of the public domain. Patents cannot be extended beyond their initial term – they arose as a way of governments encouraging innovation; essentially we agree to keep inventing stuff for the good of mankind in exchange for a period of state sanctioned selfishness in how that invention is manufactured and sold.

Patents are territorial – only good for the countries they’re granted in – but a number of international agreements exist which allow. In the EU we have the European Patent Office where a single application covers 36 nations, and for the wider world the Patent Cooperation Treaty covers 130 countries. In both cases you have 12 months from your ‘home’ filing date to extend internationally before it is considered a new application – this can be important as your initial filing date is considered to be the date from which protection becomes effective.

Check out James Cameron’s platform for stereoscopic image acquisition (also known as a camera mount) for example and improvement in velocipedes (also known as bicycles) for something a little more old school.

Registered designs

Protects the appearance of products for 25 years.

For a long time it has been recognized that the appearance of a product can be the key to it’s commercial success – may I present, as evidence, anyone who buys anything from Apple.

A registered design gives its holder the right to prevent anyone else making or selling products which look and feel the same as the registered design. It covers tangible, physical, crafted things (like the famous coke bottle) as well as conceptual, aesthetic things (like the famous coke logo).

Registering a design is quite straightforward – compared to a patent application – as it does not involve any detailed scrutiny by an examiner. Apply to the Intellectual Property Office and, within 3 months, you could be the proud new owner of a registered design. Also unlike patents, you have 12 months from when your design first becomes public to register it; with a patent when it’s out it’s out!

Design rights

Protection for appearance of products without any special application being made (for example copyright).

Design rights are a collection of automatic protections which apply to various original works. In practice they work very similarly to registered designs – and apply to similar works and materials – but do not need to be applied for in order to take effect.

The subclasses (if you want to be geeky about it) are:

- UK design right – protects shape and appearance, except for surface decoration, for either 15 years from the creation of the design or 10 years from the first time the design was marketed.

- Community design right – similar protection to the UK design right and also covers surface decoration, however it is only valid for a maximum of 3 years from the date the design was made public.

- UK copyright – can be thought of almost as the opposite of UK design rights because copyright covers surface decoration (not form and function) and ‘artistic’ qualities. In force for 25 years from the end of the year in which the design was first marketed.

If design rights apply automatically why would you pay to register a design? If you rely solely on automatic design rights then you must prove that a similar product was copied from your protected material – with a registered design you can prevent another party from making or selling something similar whether they copied you intentionally or by coincidence. It’s pretty easy to determine that two items are similar, but a lot more difficult to prove why.

So that’s our 4 identified types of IP.

In the technology and software business you’ll mostly deal with copyright and patents. In my next post I’m going to walk though patent application process since copyrights kind of happen on their own and the granting of a patent looks simple from the outside but turns into quite an arcane art.

And finally, now that we’ve covered formally establishing and reserving rights using the various offensive and defensive legal tools available to manage IP, the thought I want to leave you with is that there is nothing quite like good citizenship. Treat the property and creations of others in the same way as you’d like them to handle yours – patents, copyrights, or not.

Friday, 19 November 2010

Steriods for Signups

So, for the quick review, the registration funnel is basically the set of steps a potential customer traverses on their way to becoming an actual customer (converted) and typically starts with a site hit and ends with an active user account. What these steps consist of varies with the nature of each business and might include things like a shipping address or a credit check along with the basics such as username and password.

The problem every web business faces is that the registration funnel is essentially a very lossy process. For example; of every 100 site visitors, 50 will start the registration process, of that 50 25 will complete the process, and of that 25 10 might go on to place their first order. Even with the best husbandry many web businesses have single digit conversion rates. With marketing on the web becoming more sophisticated and SEO/semantics driving smarter access to content getting the numbers in the top of the funnel usually isn't the problem and - just like any other lossy process - there can be a big impact on the bottom line by improving the rate by just a couple of points.

So how can you juice this up?

The very first thing you need is data. Just like everything else you need to understand the flow and then you need to instrument the heck out of it before you should be fiddling with it. If you haven't already got this in place then stop reading now and get on with it - the rest of this is useless without insight.

Separate your registration process out in your head; this will help you understand and instrument it. Think through all the steps in your funnel make it as granular as possible - this gives you much more insight into where potential customers drop out and much more flexibility in how you modify the process in response. Crudely; if you're thinking visitor -> credentials -> personal details -> checkout then you should be thinking visitor -> credentials -> name and email address -> shipping address -> checkout. This doesn't necessarily mean more pages or more data for customers to enter (in fact the goal is the opposite) but it does mean than you can count these things individually to see exactly what bit of information your potential customers get reluctant about handing over and it allows you to stage things a little more (see below).

The general principle is to put the fewest barriers between your potential customers and your product as possible. This means looking at what information you're asking for, when you're asking for it, and how it's captured. In some businesses there can be constraints which have to be acknowledged; with a product which is regulated or controlled in some way there may be some external rules which can reduce your options - such as the requirement for identity verification or credit checking - but the keyword here is reduce. The registration pipeline in these types of business is often poorly managed for this reason but it doesn't always need to be; take the time to understand the details of your governance and you will usually find that you have more flexibility than you assumed. For example you might need to verify your customers identity somehow before allowing them to make a withdrawal but does that have to stop you from granting them access to the rest of your product entirely?

Nice segue into staging. One of my favorite techniques in businesses with more complex registration requirements is to focus on capturing the absolute bare minimum during an initial signup (usernames, email addresses, passwords, etc) and capturing the rest 'just in time' in line with access to features. For example; why not delay asking for a physical address until the first time a user reaches the checkout? Why not ask for payment information just before their first purchase? You don't need that data until those events and having to enter it all up front can be prohibitive especially when potential customers might not be 100% sure that you're the service they want. Also think carefully about when you want to trigger the 1st step of the registration process - there can be benefit to letting potential customers play with a little bit more of your product before hitting them up for some credentials (but you have to balance this with less complete early contact information and the risk of taking it too far and having fewer accounts because the majority of the value is available anonymously).

Usability is an important aspect here. Considering the number of screens in your signup process, the number of fields, and even the phraseology of the questions can improve your conversion rates.

Also consider the order that you're capturing information in; if you start with email addresses and you're automatically storing fields as they're completed - a highly recommended Ajax trick - then you have some actionable data to go with your telemetry. You might want to use it for a follow-up contact to see if you can claw a customer back from the edge of registration oblivion.

Another consideration when you're designing your forms is to keep in mind the sort of information users are likely to have close at hand when signing up for your site. The more esoteric (in day-to-day terms) the information you ask for is the higher the chances that a potential customer will need to go elsewhere to retrieve it during the signup process. Data always shows that anytime a customer leaves the page(s) for any reason the changes that they'll return and complete them drop through the floor. What might you not even need users to enter at all? You can pick up things like language and locale from the browser and tools like geo-IP; adjusting a probably-correct field from a list of common choices is far preferable to data entry.

While we're on forms; short and sweet is the way to go. Whenever you have to go 'below the fold' then you're better off splitting the form into multiple pages (otherwise it appears too daunting) and, when you're going across multiple pages, then label the progress. A simple 'page X of Y' can work wonders setting expectations.

And finally, if there is a relevant infrastructure for your line of business (meaning that you can trust it and that a portion of your users are likely to be members) you can consider using an identity service, such as OpenID, to implement a kind of 1-click signup and then just capture the additional information you need to operate the account.

Change it and see what happens - after all you're collecting all the data you need, right? If you're crafty enough then you can do some A/B testing with alternate pages or different text. As long as you're measuring the process you will really quickly find out what's better and what's worse.

Monday, 4 October 2010

MVP in the Enterprise

Minimum Viable Product (MVP) is a well understood concept in startups. It is all about distilling your features down to the barest of essentials – those things which really make your product your product - in order to get something out rapidly and be able to quickly iterate guided by feedback. From working at both ends of the startup-to-mature-business spectrum, it occurs to me that the enterprise could learn a thing or two from its lighter-weight cousins.

To broadly generalise the circumstances I’ve seen:

We’re pretty good at this MVP thing in early stage startups. Mostly because, as we plan an iteration, we are fully aware that we might not be around for another iteration so whatever goes into this one has to count (in fact it might count for everything). We think lean. We’re typically good at serving our customer’s most immediate and pressing needs.

In the enterprise we have the luxury of working with the confidence that, even if the immediate next set of features don’t quite hit the sweet spot, we’ll be around for many more iterations yet before times start to get tough. We think deep and wide. We’re typically good at serving a big strategic master plan.

Being able to take a longer term view of a roadmap is definitely an advantage and having to spend time worrying about things like scalability is a nice problem to have, but this doesn’t mean that we can’t also think lean. In fact some of the most value I’ve added has been in the amount of work I haven’t done...

It can work in big business.

Recently I looked at a system to capture and analyse certain customer activity in order to get an earlier prediction of lifetime value and make data-driven cross selling decisions (which ought to push up average revenue a notch) and, on the surface, that seems like it’s worth the pretty hefty licensing, integration project, and infrastructure costs. We started off modelling it and running the numbers; at first synthetically and later with real data. What we learned through this early prototyping is that those features which were initially so attractive made very little difference to our business, however our little robot was uncannily good at identifying fraudulent activity. So we switched the direction of the project, chose an alternative platform, saved a bunch of money and got some functionality which genuinely benefitted us. Sometimes you know what the real benefits are going to be up front, sometimes you surprise yourself along the way.

We’re also planning to introduce a pay-as-you-go commercial model for our feed products. When you add up a metering system to watch client consumption, a dynamic pricing system to set tariffs, a billing engine to produce the required invoices, and some reporting tools to keep an eye on its performance it starts to become a fairly significant undertaking. Will customers like it? Will it work like we hope (add top-up revenues to committed subscriptions) or like we fear (cannibalise commitment for shorter term hits)? The best way forward in these circumstances is to ask what is the absolute minimum amount of work I can do to see if this works? As it turns out we could do a some basic instrumentation (to get simplified metering), use some static pricing, and do the billing manually. Net result? A much smaller piece of work – useable in production with real customers – demonstrating how successful it’s going to be. Now we can build on this with further iterations until we have the fully-featured and refined version we first dreamed up.

There are many more examples, some of which have worked out just fine – so we’ve kept building on them until they were feature complete, fully automated, and enterprise quality. Others have failed – so we’ve cut our losses (fail fast fail cheap; writing off a few thousand not a few million) and moved onto something different which did turn out to be a winner.

Just because we have the budget and the appetite to do the whole shooting match right away doesn’t always mean we ought to.

The obvious risk here is becoming too short sighted with your plans. The secret to making this work is to imagine big but plan small – keep a long term roadmap and have a clear vision of where you want all your products to get to, but take small, tightly scoped steps along that path. Stop and evaluate frequently, adjust big picture where necessary, rinse and repeat.

Monday, 20 September 2010

Mechanical Sympathy

In the world of motorsports ‘mechanical sympathy’ is the measure of a driver’s impact on their vehicle. As well as fuel economy it is probably well understood by most people that your driving habits do have some impact on how long your car is likely to last, how often it needs attention, and how quickly the parts will wear out. The world of professional drivers is no different, except that excess punishment of the car can mean that vital few more seconds spent in the pit lane – which can cost a racing team a lot more than just this year’s annual service coming up sooner.

Mechanical sympathy attempts to quantify that impact and allows teams to acknowledge it and work on balancing car wear against squeezing that last little bit extra out of it.

I did a motorsports driving course a while back (number of formula 1 events participated in since training: 0 – number of speeding tickets around town since training: 1) and was mercilessly rated in this category. I guess that explains the frequency of servicing that my long-suffering saloon seems to require…

As an outsider to the world of motorsport the importance of certain metrics is immediately obvious – lap times or time spent under power etc – but why measure drivers on something mechanical? These guys don’t fix their own engines, swap out their own gearboxes, or tune their own brakes; that’s someone else in the team. But, as drivers, they do have a direct impact on how often this needs done, how severe it’s going to be, and how expensive it will be to do – and that has a direct impact on winning and losing.

So why don’t we measure the non-IT people in our businesses on their impact on technology? I’d like to introduce the concept of technical sympathy.

I think that people in our businesses should have at least a small part of their KPIs relate to technology. We’re not expecting them to be developers or sysadmins – in the same way that drivers aren’t expected to be mechanics – but we have to acknowledge that they do have an impact on this stuff (probably more than they realise).

Good stakeholdership can make the difference between a well-run project hitting time and budget and a chaotic piece of work drifting on endlessly. Considerate use of systems can avoid the need for expensive environmental controls and the wasting of shared resources such as disks and tapes. The costs and turnaround times of support can be dramatically different with more personal responsibility and better use of self-service at the desktop.

In almost every company I have worked in we’ve measured engineers on business knowledge and company performance to some degree, yet we never seem to have thought of the reverse even though business behaviours can have a profound effect on the cost and quality of technology.

Wednesday, 15 September 2010

The Product Management Boundary

Talking to a few of my industry peers (web CTOs and CIOs) about what they do, and to a few CEOs about their expectations, something that’s becoming clear is that we’re increasingly being expected to know what to do, not just how to do it.

Traditional IT uses that age old you-give-us-requirements–we-give-you-back-[mostly]-matching-systems paradigm or variations on that theme. Something we do would typically have a sponsor who dreams up a course of action and a handful of stakeholders who detail it out. What you call those people will depend on whether you think you’re doing agile, RUP, waterfall, etc but typically you’d place them in ‘the business’ rather than technology.

That seems to be changing.

Less and less are we being handed requirements documents or project specs and then going off and doing work to order. Now we’re being asked things like; how do we reach new users? What things can we do to increase wallet share? Should we be doing something with social media? How are we going to internationalize this product? Yeah, that’s right, we’re finally dealing in problems not in todo lists, and - in a trend which is gaining popularity - product management is increasingly being based inside the technical delivery teams.

The days of a business giving us defined work and us delivering projects against it are going to come to an end. A pessimist might suggest that this is ‘the business’ escaping responsibility for defining it’s future. I’d simply argue that technology is an integral part of any modern business, not something else extra and external, and since we’re all part of the same ‘business’ anyway then why shouldn’t we take our fair share of determining the strategy?

I think this is pretty awesome and, in some cases, overdue – after all, don’t we want a bigger influence over what the future of the business looks like and how we get there? Do it CxOs!

Thursday, 29 April 2010

Technical Debt Credit Rating

Outlawing technical debt is as foolhardy as always cutting corners - sometimes the right thing to do is to take a hit to get something out sooner or in a certain shape - the problem is in the repayments; in other words, they often don't exist. And if you don't go back and sort your hacks out early they tend to accumulate in the system and before you know it developing on it is like moving through treacle (and the treacle occasionally catches fire). Everything else you do takes that much longer and is that much more expensive (and those are business metrics) and can have unintended consequences - it's a crippling burden just like its financial counterpart.

I have a rule - no one is allowed to take technical shortcuts through a project [where that = incur some technical debt] without showing where, in the same plan, they go back to do some refactoring so that our long-term assets remain sustainable. We're pretty lucky at Sporting Index; most of our stakeholders value technology and recognize how critical it is to the business, so it's a conversation I rarely have to have - but I know many other companies are less fortunate.

So now I think I have a better idea. It came to me while I was thinking about why, if technical debt is so similar to real debt, it doesn't regulate itself in the same way - and I think that's becuase there is no concept of creditworthiness in technical debt, in other words no assessment of a team's ability to 'repay' a quality compromise (read: loan of functionality to the business ahead of when it otherwise would have been ready) alongside all the other outstanding quality compromises that they already have.

But we might be able to simulate that...

Imagine giving each product manager a 'credit rating' of, say, 3 - meaning they could call for unsustainable technical shortcuts 3 times as they worked with the delivery team to determine their solutions. Once those 3 debt points were used, that product manager would be unable to encourage the team to make further quality compromises until at least one of those was paid back. If you have product managers with a demonstrated track record of revisiting earlier deliveries to address technical debt then why not give them 5? A higher creditworthiness ought to enable an individual to take on more concurrent debt as we can be more confident that they'll come back to service it.

I pretty much guranttee that any product manager's cavalier attitude towards shortcuts would change and they'd suddenly treat technical debt as the instrument it really is and use it only where it mattered materially. That, ladies and gentlemen, is a feedback loop.

The downside is that you'd have to be better at tracking this sort of thing and, like any other method, it'll need some discipline when a product manager with maxed out technical debt points wants just one more shortcut. If you've ever had to maintain a spaghetti codebase (as most of us have at some point) then you'll know that these things need closely policed anyway, so perhaps being forced into formally tracking it isn't so bad.

Wednesday, 28 April 2010

Nobody Wants Computers

Many people turn up to conferences or SIG meetings and ask me how virtualisation or a centralised inventory database or VPNs (or pick something) will help their company. Misguided. My response is always the same - what is your business case and what benefits are you expecting? I do get quite upset when I don't get a good answer to that, because it means someone somewhere is cooking up some technology for technology's sake.

Sales functions are excellent at creating a need around a product they sell - great if you're in that business and I used to be - but it is the functionality your organization really needs that should matter. Talk to me about outcomes, goals, what you want to be able to do from a business capability perspective, and then the right technical solution will fall out of that.

Contorting business processes to fit a specific technology or vice versa - i.e. doing it backwards - only ever works when combined with a healthy dose of luck.

Friday, 23 April 2010

The ISO standard for business plans

Don't agonise over format and presentation - the vital thing is to intimately know your key facts and be able to provide a logical narrative for them. What are your costs? Where does the revenue come from? Who are your customers and how big is the market? How soon will you start bringing in revenue? How is your product different from any competitors (current or future)? What does it cost you to acquire new customers and what is their lifetime value? Have you done this before and who do you plan to work with? Even if you just talk through it you're always better off knowing those things inside and out than having a 200-page glossy document.

And when I say that a business plan matters less than you think it isn't because investors won't want one - they very much will - it's because in the early stages of a new idea what matters most is working product. The best, most detailed, most polished business plan in the world will always be worth much less to a potential backer than a pretty basic, hacked together but functional, beta product.

Wednesday, 31 March 2010

The Paradox of Freemium

Firstly, for those who may have spent the last few years in a cave, I broadly define freemium as giving away something of substantial value along with an associated upgrade/expansion path which returns benefit to the organisation.

This is already commonplace. So many of the everyday tools I use have an element of freemium to their business model; google apps, zen agile, bitbucket, linkedin, mockingbird, a number of podcasts (which lead to paid-for books or other products), and of course almost every iPhone app I see these days has a fairly comprehensive ‘lite’ version.

For a long time we’ve given away tightly limited trial versions, exposing a very small subset of the functionality (or usage time) in order to coax users into a purchase to unlock the rest, and freemium is almost a reversal of this. Give away quite a rich set of functionality with no expectations, and you’ll pick up a group of buyers for that additional stuff on top.

Making this happen comes down to product design; you have to make sure that you hold back something(s) compelling enough to encourage purchases while making sure that your base product is functional and complete enough to be of significant utility on its own. There are so many ways to slice this, and sometimes the differences don’t even need to be rendered – you might simply impose several distinct licensing terms (free for academic or home use for example).

In one of my all-time favourite Ted Talks, Dan Pink says:

"The mid 1990s, Microsoft started an encyclopedia called Encarta. They had deployed all the right incentives. All the right incentives. They paid professionals to write and edit thousands of articles. Well compensated managers oversaw the whole thing to make sure it came in on budget and on time. A few years later another encyclopedia got started. Different model, right? Do it for fun. No one gets paid a cent, or a Euro or a Yen. Do it because you like to do it.

Now if you had, just 10 years ago, if you had gone to an economist, anywhere, And said, "Hey, I've got these two different models for creating an encyclopedia. If they went head to head, who would win?" 10 years ago you could not have found a single sober economist anywhere on planet Earth, who would have predicted the Wikipedia model."

I think those same sober economists would probably have said much the same thing about freemium, and probably much more recently. Getting customers to pay for your product by first giving most of it away wasn’t common sense – and maybe it still isn’t – but you certainly can’t ignore the evidence that it works.

Friday, 26 March 2010

Encouraging Profitable Usage

I was particularly interested in the stats near the end - in a crackdown on gold farming they managed to drop CPU utilisation 30% through a 2% drop in players (banned accounts who were violating these terms). To paraphrase that; 2% of the player base [revenues] were creating 30% of the load [costs] and that my friends, is what I call unprofitable usage of a product.

When you read that last sentence it makes perfect sense, however so few of us on the web think this way. How often have you looked up your top workload creators (page impressions, transactions) and your top revenue creators (purchasers, subscribers) and compared the two? How sure are you that your costliest customers - that you are probably supporting a collection of CPUs to service - are not marginal or worse in terms of value to your organisation? With sites more data rich than ever (read: more back end work per view) and screen-scraping a more widespread way to acquire content it's worth working to discourage this behaviour or at least make conscious decisions to allow it.

This thinking should be taken all the way back to product design - on the web we tend to emphasise users/visitor/subscribers without really thinking through what constitutes profitable usage.

It's not just about nailing people who are out to exploit you either - as a long time data provider my biggest issues have usually been well-meaning customers with lazy integrations. If you're going to build a client on top of a web API it's quick and easy to poll the bejesus out of it round the clock and then react to data in the responses rather than, for example, get a schedule of 'interesting' data and dynamically set up threads pick up smaller changes to discreet items on separate and appropriate timers. Take trades for example; why hammer a Hang Seng Index Options feed after 4:15pm? Or how about our feed - do you need 5 prices a second for this weekend's football fixtures on Tuesday or would hourly pre-match odds and squad changes be more than sufficient that far out? A slightly trickier initial integration but a better and cheaper product (for both parties) thereafter.

And finally I've always found it more effective to encourage good behaviour than discourage bad behaviour. Sometimes this can be as simple as an SLA which guarantees a superb latency up to a certain number of requests and creeps out in bands beyond that. Other times this can be purely commercial - why not extend better pricing to customers who genuinely cost you less to service or a tiered revenue share to those who contribute more to the partnership?

Wednesday, 6 January 2010

The hidden wisdom of Kevin McCloud

Reading some of the advice, there is a lot that can be applied directly to software projects. There is a section on 'how to behave with your team' which is aimed at helping people keep their building sites productive - but the advice translates well to technical projects. Here's a couple of my favorites along with my join-the-dots:

"Don't give verbal instructions on site unless they've been agreed with your consultants and they're backed up in writing. If you just issue verbal instructions, you risk confusion and possible extra costs."

This is a top one for me - especially in the agile world where many interpret 'agile' as 'make it up as you go along' and then end up disappointed. I think maximizing interaction between delivery team and customer team is a good thing especially when both sides recognise the boundary between clarification and change in in-flight work.

"Do take time to prepare detailed written briefs setting out all your requirements for all your consultants. A good brief is an essential part of the design process."

One of the simplest formulas the govern all project delivery (hardhat or mousepad) is that the quality of what you get out with never exceed the quality of what you put in - yet this seems to escape so many of us so often. What you invest in clear instruction and regular contact with developers is a key variable in how happy you'll be with the results.

"Do allow your experts the freedom to do their jobs. Stand back from the project and enjoy your role as client; making decisions and hanging around, generally being a good egg and imbuing the world with optimism and excitement."

I don't exactly advocate stakeholders 'standing back' from a project, and I don't think that's what Kevin means either. Don't micromanage your delivery team and, as a customer, be sure to perceive the difference between decisions you should make (and don't let the team wait for those) and decisions the team should make (and let them use their skills and experience to make them).

"Don't listen to other people outside the professional team. You'll only end up getting very confused."

External feedback and extra ideas are good, but remember that an engineer knows his business best and don't fall into the trap of listening to someone else simply because you like their answers better. I consider myself relatively smart but even I'll say all sorts of wacky things when I don't have any skin in the game...

There are a couple of other sections with close analogies to technical projects - how to be a perfect customer and how to put a good brief together - which I think are 2 other critical ingredients to any successful engineering project (construction or software) but they'll keep for another post.

Wednesday, 16 December 2009

Introducing Sporting Index Super Simple Integration

This year we decided to give our B2B customers an early Christmas present - SSI.

Sporting Index (well, really Sporting Solutions, our B2B brand) provides pre-match and in-play pricing and content to fixed odds bookmakers for hundreds of markets across 16 sports with more events from more jurisdictions being added almost every month.

Traditionally we’ve done this by pushing XML documents around over reliable transports and leased lines. This works very well and there is nothing inherently wrong with this solution, but we weren’t happy that customers had to install expensive fixed lines and associated hardware, and our back end is capable of producing multiple-thousands of price changes a minute – well beyond the rate at which some of our customers can consume them.

On top of this, our customers wanted the low latency and reliable updates that come with a push solutions, but also the easy integration and flexible client-side controls that comes with a pull solution.

Well, you asked for it and you’re the customers, so let’s unwrap this bad boy.

Super Simple Integration is essentially a RESTful web services API available over the good-old-fashioned Internet. The feed is as easy to consume as you’d expect from any web API, and we’ve spent a lot of time on the data formats and doing some clever pub-sub tricks in the background – thus all the benefits of the heavyweight XML services but through an integration which is quick and easy to get to grips with.

There’s a lot to this, so let’s just cover two of the most common use cases:

Get Content

Our content products can be used to populate websites with upcoming fixtures and players, and to power pages or widgets showing points, corners, goals etc as they happen in running matches.

Content products are mostly stateless and work on a fairly simple request-response model, which can mean no integration work at all. Well that’s half true – you still need to consume the data from the API – but you don’t necessarily need to build a repository on the customer side or have to match up schemas.

Let’s say that wanted to build a little scoreboard for my site to show my visitors the progress of a live England v New Zealand rugby game;

You get the content you want, as often as you want, delivered back in name-value pairs. There are also a couple of methods to call to list out what sports and events are available, so you can pick out what to pull into your scoreboard app.

Pretty basic stuff so far, where it really gets sweet is how we implement real time price streaming.

Get Prices

Our price products can be used to price up sports betting markets, either as a risk advisory tool for human operators or a totally automated pricing service, and cover a wide range of sports in-play with high fidelity price output.

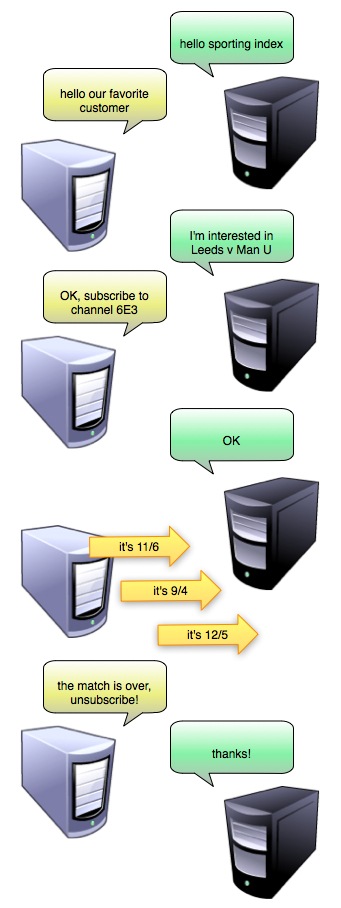

In price products - particularly once fast paced events turn in-play - state and reliable delivery become important, but we’ve enabled our customers to nicely sidestep the costs and technical complexity this usually involves. When your API client registers interest in pricing up an event we build you your very own data object, which we call a channel, and then it works like pub-sub system. Our back end pricing engine is event driven, and as events occur which trigger price changes, those changes are accumulated in the channel you’ve subscribed to and delivered out to your system in real time over secure HTTP;

This puts quite granular control of the product into the client-side’s hands, allowing you to programmatically build object(s) with any combination of markets and data that you’re interested in and then subscribe to your very own private feed over familiar transport.

By accumulating interesting data into user-defined objects this way we also buy back the robustness that dedicated WAN links gave us – if there is a network disconnection the client simply re-establishes an HTTP connection to the API and picks up where it left off – no lost updates or re-synching required.

That’s SSI in a nutshell. It’s the easiest integration in the industry, and from our perspective it scales out nicely - being just a collection of smart web services - and also enables us to accelerate the building of data-driven products for our own business too.

Saturday, 3 October 2009

I think you might have it backwards

One of the benefits of managing projects using, for example, SCRUM is that you're not burdened with having to define all the requirements up front and plan out all the tasks and times for all the resources for 6, 12, 18 months. Trying to precisely define everything a project needs up front and trying to plan for every dependency, holiday, resource issue, structural or strategic change over a long period of time proves again and again to be an impractical task.

Enter agile.

Suddenly we don't have to worry about the detail of every change and every movement over an entire year, and we're introducing a whole bunch of flexibility. Where it goes wrong is not fixing any certainty in the delivery process at all.

Agile is about certainty and detailed planning, just detailed planning over a period which is possible to predict. Who knows what'll happen over a year, but you at least have a fighting chance of planning out the next 2-4 weeks will some degree of accuracy. Beyond that you can keep plans and requirements fluid and high level, netting you the right balance of fixing doable deliverables and keeping flexibility.

Software delivery needs certainty to happen - you have to be able to rely on some requirements and some resources over some time span in order to make progress - and agile isn't about not having any, it's about having it on terms you can foresee.

Sunday, 27 September 2009

Screen Scraping for Dummies

The piece of software that does this scraping is commonly called a robot, or bot, and it is really just an automated web client that accesses and uses sites in the exact same way as it's fleshy counterparts, just with machine precision and repetitiveness. A bot may be a large and complex program running on a server with it’s own database etc, or as simple as a script running in a browser on a desktop.

This is typically regarded as undesirable behavior by many sites because, in most cases, it’s a source of load and associated with unprofitable usage. Whenever we draw a page impression, which we’ll do for every bot hit just as we do for every human visitor, we consume web server time and, worse, back end time. When we structure highly functional pages loaded dynamic content we can create a very engaging user experience, and all that functionality is built on plenty of back end work and data. When used at regular human pace that's usually OK, but under the relentless rate of hammering robots are capable of, it starts to become expensive.

If you've got a case of bots, you have to start by identifying them. Their repetitiveness and flawless precision is, in this case, their downfall and we can usually spot them easily through proper analysis of web logs - no human user is as mechanically regular, millisecond quick, and consistent in journey as your average droid.

Spotting droids isn’t too hard, but then you've got to decide what you're going to do about it. Most scrapers aren't malicious and often don't realise the headache they're giving you. In the first instance it's best to try some detective work, see if you can find out who they are, and get in touch. Domain registrars can be a great resource for this, but don't overlook the obvious - maybe they even have an account with you if data they're using requires signup to view.

Beyond that it gets tricky, and can easily turn into an IP address blocking arms race. With some caching finesse or smart layer 7 rules you can throttle bot activity to more palatable levels, or persist them to their very own node that they can thrash all day without impacting the experience for the rest of your users.

If robots are a very big problem for you, then try and take it as a compliment on the value of your data and perhaps consider publishing it via a productised API or feed - if you make it simple enough to consume, then most scrapers will willingly change over to a more reliable integration mechanism and perhaps even pay you for it.